Let’s get a bit meta and think about our brains for a moment.

The brain functions as the coordinating centre of sensation, nervous and intellectual activity. It is composed of approximately 100 billion neurons that constantly restructure themselves each time we learn new information. The organ is so strong that it can produce enough energy to power a light bulb.

But what exactly does this mean for writers? Neuroscientists, psychologists and writers are only scratching the surface on research into writing and the brain – so let’s take a closer look at what they’ve found so far.

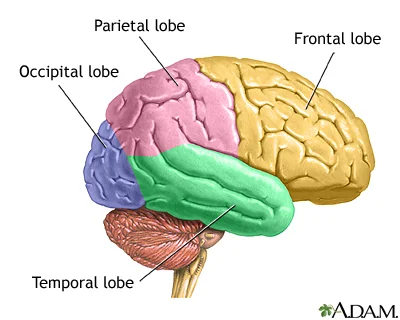

To appreciate how writing affects the brain, we first need to understand the functions of its four major lobes.

Frontal lobe

The frontal lobe modulates the feelings and emotions that make up your personality - the characteristics that shape your personality and make your writing distinct. Broca’s Area, a small region to the left side of your frontal lobe, is essential in the writing process as it converts thoughts into words.

Parietal lobe

The parietal lobe integrates sensory perception – such as touch, taste, spatial sense and navigation. This section of the brain also deciphers visual and auditory signals, which supports language processing. People with parietal lobe damage may lose the ability to understand spoken and written language.

Occipital lobe

The main function of the occipital lobe is to decode visual information, so this lobe is active while you’re reading these words. Containing most of the visual cortex, the occipital lobe is associated with form, movement and colour. This part of the brain is essential for writers as it allows us to transform a picture into a thousand words.

Temporal lobe

The temporal lobe is involved in hearing, language comprehension and verbal memory, as well as high-level visual processing (perception and recognition of objects and faces). Temporal lobe epilepsy has been linked to hypergraphia (a behavioural condition characterized by an intense desire to write), which reportedly affected Lewis Carroll, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and the poet Robert Burns.

Studies on writing and the brain

Writers have the ultimate power to influence others.

Scientists have found that storytelling can effectively plant emotions, ideas and thoughts into to the brain of the reader. Research conducted at Princeton University, led by Uri Hasson, placed a woman in an MRI scanner and monitored her brain activity while she read a story out loud. Later, they played the recorded story to a group of volunteers while scanning their brains – and found that their brand activity synchronized. When the reader’s frontal cortex lit up with activity, so did the listeners’. The storyteller was literally planting ideas, thoughts and emotions into the listeners’ brains.

Hasson also found that the better listeners understood the story, the more their brain activity dovetailed with the speaker’s. This is why simplicity and clarity are essential to good copywriting, where our goal is to sow thoughts and desires directly into readers’ minds.

Experienced writers’ brains work on a different level.

At the University of Greifswald in Germany, neuroscientists tracked the brain activity of both budding and experienced writers while they wrote a piece of fiction. Martin Lotze directed a team of researchers to monitor the networks and connections utilized by writers’ brains as they drafted their stories.

The team discovered that for experienced writers, the task becomes instinctive and their brains use short cuts to economise activity while working on a subconscious level. This finding seems to hold true for John Boyne, an experienced writer, who wrote his first draft of The Boy in the Striped Pajamas in under three days. He asserts, “I think a lot of my writing comes from the subconscious. The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas was an unusual writing experience – no sleep for three days and constant writing.”

For writers with little to no writing experience however, the study showed activity in the occipital lobes, meaning their minds were focused on decoding visual information. This suggests inexperienced writers were accessing and recalling visual snippets of memories, imagined scenes and other source material as they wrote.

False colour montage of sagittal brain scans from two participants in the Johns Hopkins study, showing lesions causing difficulties in speech (left) and writing. Photograph: Johns Hopkins

Writing and speaking are supported by different parts of the brain.

At Johns Hopkins University, Cognitive Scientist Brenda Rapp and her team of specialists published findings in the Journal of Psychological Science suggesting that speaking and writing may be controlled by different parts of the brain - not just the motor functions involved in each task, but also higher-level aspects of language, such as how we construct words and sentences.

“We found that the brain is not just a 'dumb' machine that knows about letters and their order, but that it is 'smart' and sophisticated and knows about word parts and how they fit together.... It’s as though there were two quasi independent language systems in the brain,” explains Rapp. As part of her team’s research, they studied subjects who could speak perfectly coherently but when writing their words become jumbled, or vice versa – indicating different areas of the brain are at work during the two activities.

Vivid writing makes readers feel every word.

Scientists have established that the classic language regions of the brain - Wernicke's area and Broca's area - are active when we interpret written words. However, recent research indicates the power of narrative can simultaneously activate many other regions of our brains, allowing readers to share characters' experiences on a mental and emotional level.

A team at Emroy University studying the effects of writing on the brain discovered that the parietal lobe, responsible for sensory reception, activates when we read or listen to textual metaphors. However, Annie Murphy Paul, journalist and consultant commented in her article Your Brain on Fiction, "parts While metaphors like 'The signer had a velvet voice and 'He had leathery hands roused the sensory context, phrases matched for meaning like 'The singer had a pleasing voice and 'He had strong hands' did not." This means specific textual references are recreated in readers brains, however more abstract descriptions (such as "pleasing" or "strong") don't produce the same effect.

The scientists have spoken! Good writing recreates feelings emotions and other sensations directly in the readers minds. Armed with a keen understanding of how the brain processes language, skilled writers can literally plant ideas in your head - and only get better with experience.

[Picture from @reimaginepr]