We’ve always been taught that two negatives don’t make a positive – unless you multiply them together, because math is weird. However according to most English teachers, double negatives are considered heresy. What’s the point of them when you could simply substitute a positive word to mean the same thing? While that’s true most of the time, what if we told you there are instances where the use of a double negative are actually justified? With the help of Caroline Taggart and J. A. Wine’s book My Grammar and I (Or Should That Be ‘Me’?), let’s explore the rules behind negatives… and when the illusive double negative can shine

Are double negatives really worthless?

From the image of Bart Simpson writing on the blackboard above, you can already see there’s a glaring problem when you use more than one negative in a sentence – it twists the brain and muddles the meaning of the sentence. According to Robert Lowth, the Bishop of the Church of England in the 1700s and an Oxford Professor of Poetry, using “two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative.” In other words, it’s a rare instance where two negatives do indeed make a positive – in which case, it’s often more prudent to simply use a positive and eliminate the redundancy.

Let’s take a look at some examples:

A. “That silly boy can’t do nothing right.”

B. “There shouldn’t be nowhere that the scoundrel can hide.”

C. “The mayor is barely never wrong.”

At a glance, you’d probably imagine a cowboy or sheriff from the Southern United States uttering these lines in an old western movie. It’s got a rustic charm to it, but it don’t mean none of them sentences are right! The first is blatantly incorrect because the speaker is criticising the boy’s incompetence – if you were to apply Lowth’s rule, the sentence’s actual meaning is misrepresented because he/she is accidentally saying the boy can do anything right. As for B, it’s clear that the speaker wants to say that the scoundrel can’t hide, so using both shouldn’t and nowhere together is a pointless redundancy.

In C, the problem is less apparent. Some might even argue that there isn’t a double negative! However, barely is indeed classified as a negative (as are the adverbs hardly and scarcely according to this list of words from Grammarly). Although you can apply Lowth’s rule, this is a case where it’s not immediately clear whether the speaker intends to insult or compliment the mayor. Since the sentence can be interpreted in both directions, it appears that Lowth’s rule isn’t as universally applicable as he thought! So how do we discern what the writer or speaker means? We’ll cover that in the following section.

By now, it’s quite apparent that double negatives can do more harm than good (unless emulating a southern style of speech). This begs the question, are double negatives useless? Well, not entirely! According to Taggart and Wines, “double negatives are permissible – indeed, useful – when they convey cunning nuances of meaning.” Much like a figure of speech, you need to be smart about when to use them!

“It’s not unusual to be loved by anyone,

It’s not unusual to have fun with anyone,

But when I see you hanging about with anyone,

It’s not unusual to see me cry…”

One shining example is Tom Jones’ legendary song “It’s not unusual”. Of course, the lyricist could have simply written “it’s common to be loved by anyone” or “it’s common to have fun with anyone”, but you can’t deny that the song sounds a lot catchier when the double negative is used. More importantly, you feel more sympathy towards Tom Jones’ affection for his crush.

Aside from its use in music, consider this next example from Taggart and Wines:

“I wouldn’t say I don’t like your new house.”

There are times in life when you want to be gentle with your words. Rather than bluntly expressing distaste for your friend’s house, you could use a double negative to do the same with more tact – which carries the subtext of “I am too polite to admit that I hate it.”

Furthermore, double negatives “are allowed for emphasis when they belong to different phrases or clauses,” Taggart and Wines explain, like so:

“I will not give up, not now, not ever.”

“You don’t ask for much, no more than the rest of them, anyhow.”

Much like an epizeuxis, using a double negative hammers home the point and expresses how adamant you are about something. Repetition is one of the most powerful literary devices after all!

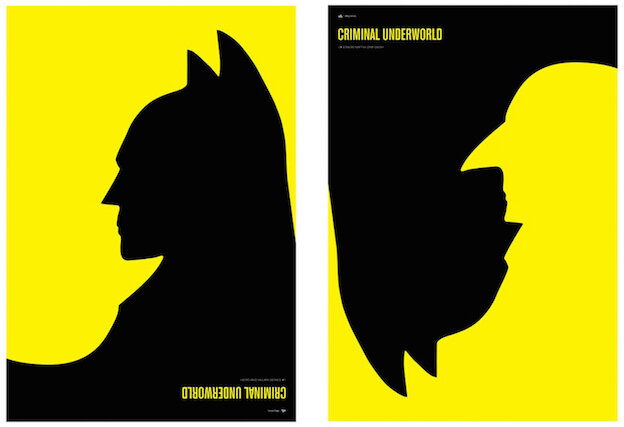

Double negatives offer dual interpretations of a sentence – like the clever use of negative space in a picture to create two distinct visuals (ie. Batman or the Penguin depending on your orientation of the image above).

A flexible interpretation

Sometimes, double negatives can create unclear meanings – as illustrated by the earlier example with the mayor. To determine the correct interpretation of a double negative, Taggart and Wines point out that you must pay attention to the context and intonation. Let’s say you and your buddies are watching the latest beauty pageant, and you ask your friend how he’d rank one of the contestants.

“She’s not unattractive,” he says.

Is the contestant attractive or not then? If your buddy places emphasis on the un, it could mean he thinks the contestant is neither ugly nor beautiful. Inversely, if he emphasises on the not, it could mean he thinks she’s rather pretty!

Here’s another example:

“That’s not bad.”

Ah the classic not bad. One of the most commonly used phrases that most people don’t even realise is a double negative! Again, we need to examine which part of the double negative is emphasised when it is read aloud. If not is stressed, then it means things are going pretty well! Alternatively, if bad is stressed, it means things could be better. See how things can get a bit confusing when we look at double negatives from a text-only perspective? It’s one of the reasons why crafty writers are fond of double negatives – it’s easy to pretend to like something while secretly bashing it and “politely” avoiding confrontation altogether!

Double negatives, while usually considered poor form in grade school, do have their uses every now and then. They can be a fun literary trick to get people to look at things differently, especially if they blindly trust in Lowth’s rule. If Tom Jones don’t got no problem with it, then neither should we!