What do Nigerian princes, your “buddy” Dave (who you haven’t spoken to since high school) and snake oil salespeople have in common? Whether they’re peddling a job opportunity, a multi-level marketing scheme or the perfect set of cruelty-free non-FDA approved lotions for your skin type, they share sales pitch tactics designed to persuade and potentially deceive the unwary – some of which are used legitimately in marketing as well! Join Wordsmith as we take a closer look behind the psychology – and language – of deception.

Professional sceptic James Randi debunks the reasons why we fall for fraudulent acts and irrational beliefs.

The liar’s lingo (or lack thereof)

Have you ever received scam emails that are worded so poorly and sound so outrageous that you can’t help but make fun of them? These low-effort scams fool only the most gullible, and the shockingly bad spelling and grammar are a dead giveaway. Let’s take a look at a typical scam email:

Seemingly written by someone wringing their native dialect through Google Translate several times, errors in grammar, punctuation and sentence structure are a tell-tale sign of deceptive writing. In particular, pay attention to the inconsistent verb tenses in the email – which shift between past and present tense repeatedly.

“Truthful people usually describe historical events in the past tense. Deceptive people sometimes refer to past events as if the events were occurring in the present,” explains Dr. Paul Clikeman on Fraud Magazine. “Describing past events using the present tense suggests that people are rehearsing the events in their mind.” Out of place punctuation, random capitalisation and lengthy run-on sentences are also characteristics of scam emails – some even containing foreign alphabets or characters to bypass spam filters.

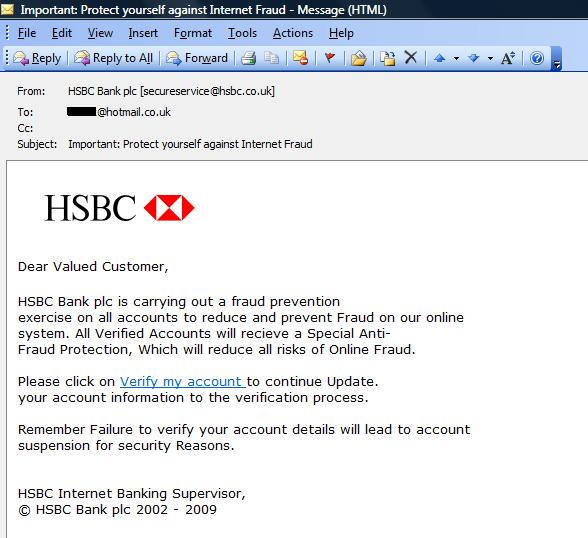

However, not all scammers pose as wealthy Africans. What should we do when cheats learn to use spelling and grammar checkers, and impersonate real institutions? Consider these emails – supposedly from “HSBC”:

If you were a patron of the bank, being notified that your accounts may potentially be suspended is no laughing matter – the official looking letterhead certainly makes the emails look more convincing as well! However, look closely at the language of these alleged verification requests and you’ll notice they have glaring similarities with the African money scam emails.

On the left, the first sentence begins immediately with a grammar mistake – “Due to recent upgrade…” The run-on third sentence is another dead giveaway.

On the right, random capitalisation on power words like “Fraud” or “Failure” are included as well – perhaps to emphasise the seriousness of the email’s consequences (more on these later), but ironically have the opposite effect.

Words of temptation

To further fake the sense of familiarity, swindlers (and marketers) often refer to us by our first names. In email marketing, personalised emails boast a noticeably higher opening and click through rate. Even if we are unsure whether or not it’s spam, the fact that it starts with our names piques our curiosity enough to read the first few lines of the email.

The same rationale is used by con artists. We feel inclined to believe that they are indeed someone we’ve met before (even if they only learned about us scrolling through Facebook or a phone book) if they recognise us and call us by name. This could be why telephone scammers using the “Guess Who I Am?” con – a trick where scammers impersonate the identities of victim’s guesses before requesting financial aid – have been so successful in Hong Kong.

Apart from your name, there’s another word that carries immense power at grabbing your attention:

“I’ve got an exciting opportunity for you…”

Whether it’s a legitimate headhunter reaching out or a conniving conman after your wallet, most sales pitches usually begin with some iteration of the above. Beyond its obvious face value definition, the word opportunityembodies the meaning of hope – the motivations and beliefs that drive us forward. Even if our current living situation is fine, the word implies that it could be made even better. On the other hand, for someone who’s life has fallen into shambles, the word will jade logic and be interpreted as a potential lifeline out of the rut.

In copywriting, great writers like Stephen King advocate the use of simple terms to get points across quickly. In sales pitches, however, powerful and dramatic words hold considerably more sway in persuasion and “compel audiences to take action”, says SmartBlogger’s Jon Morrow. Quoting Winston Churchill’s infamous rallying speech during World War II, Morrow explains that each powerful word (like grievous or suffering and God or victory) carries emotional undertones that inspire fear of losing the war and hope for the future respectively.

Using the concept of power words, consider an instance where you were comparing two (possibly lucrative and illegal) job prospects offered by “your buddy” Dave:

I’ve got an exciting job opportunity for you that matches your list of skills. Please send me your CV if interested.

I’ve got the perfect job for you and your skillsets fit the requirements to a T. Don’t miss out on this exciting opportunity and send me your CV if interested.

The first option, although to the point, is as boilerplate as can be. The second option is significantly pushier with power words that inspire self-pride and fear of missing out. Granted, you’d definitely want to know more about either job details before making a choice, but the second option sounds much more enticing.

Confidence schemes and scams are underhanded tricks that manipulate the psychology of audiences for personal gain. While we certainly do not condone such acts, there are indeed elements of scammers’ language that we can pick up to bolster our own persuasiveness. If harnessing the power of language is what your business is after, give your neighbourhood professional copywriters a call and discover how the power of language can influence your customers.